I started my research on “How to build production-ready machine learning (ML) systems” in 2019. In my first blogpost I analysed how this is different from “building production-ready software systems”. I followed that up with more blogs on testing ML applications, a quality model for AI systems (by 2022 the term ML had been replaced by the broader term AI), and an tool overview of all the software engineering (SE) “tools” I found that help AI engineers to build AI systems. By then, ChatGPT had entered the arena, and it was a true gamechanger for AI systems. All of a sudden, companies around us started asking for software systems that make use of LLMs to interact with end users in natural language, or to process natural language data. Thus, I analysed what is needed to “build production-ready LLM systems”. We have been working on this question since then, and we will keep publishing blog posts on this topic, or presenting about it in industry conferences. In the meantime, another question popped up, that is even more fundamental for the software engineer. As many of the successful LLM-based tools are actually supporting parts of the SE process. The most obvious one being the tools that generate code for us. In this blog post I will give an software engineering perspective on the most recent developments in AI. I realize that it will probably be outdated next month, but I do feel that it is important to characterize the different aspects that we need to take into account when trying to predict the future of software engineering.

What is AI?

Before we continue, we need to define AI. For this I would like to copy the definitions from Analytics Vidhya (they also have a nice picture integrating all this). Each level is encompassed in the level above it (AI > ML > DL > GenAI > LLM).

- AI: A broad field focused on creating models that simulate human intelligence to perform tasks like decision-making, problem-solving, and learning.

- ML: A subset of AI that enables models to learn from data and make predictions or decisions without explicit programming.

- Deep Learning (DL): A subset of machine learning driven by multilayered neural networks whose design is inspired by the structure of the human brain.

- Generative AI (GenAI): A subset of DL focused on creating new content (text, images, music, etc.) based on learned patterns from existing data.

- LLM: A type of large neural network model designed to understand and generate human-like language, often used in NLP (Natural Language Processing) tasks.

In this post I will primarily focus on LLMs, as they are the most influential from an SE perspective, but of course there are also other GenAI models that, e.g., generate pictures or audio.

AI & SE

As said in the introduction, AI influences SE in two different ways. This can be summarized by the two different questions that SE needs to answer:

- SE4AI: How to build production-ready AI systems?

- AI4SE: How to use AI tools to build production-ready systems?

These two sides of AI & SE are also identified by MIT’s SEI (Software Engineering Institute) roadmap for engineering next-generation software-reliant systems. Their underlying central vision is that “Humans and AI will become trustworthy collaborators that rapidly evolve systems based on programmer intent”. Their roadmap includes six technical focus areas for their research, but what about the human aspect in their vision? Before I dive into the technological developments of AI & SE, I would like to spend some time on the impact on humans of all of this.

It Is Not Just About Technology

Abrahão et al. (2025) have published a roadmap article on how AI technology is “reshaping the software engineering field, positioning humans not only as end users but also as critical components within expansive software ecosystems”. They claim that “As software systems evolve to become more intelligent and human-centric, software engineering practices must adapt to this new reality”. Their extensive analysis of software development and human-centric systems in the era of AI follows this same human-centric approach by analyzing many different human and social aspects of AI4SE and SE4AI.

From the commercial perspective Microsoft also envisions a world where AI agents will become part of the enterprise ecosystems, collaborating with human actors in teams. They call this the Frontier Firm: human-led, but AI-operated. This type of human-AI collaboration has several consequences for the human:

- we have to decide what to delegate to AI and what to do ourselves, just as we would when working with junior colleagues or interns; Dellerman et al. (2025) call this hybrid intelligence;

- we need to be able to effectively use what we get back from the AI; that requires translational expertise: combining expert judgment with inputs and guidance from AI to carry out “elite expert” tasks;

- we should preserve and enhance our own intellectual skills while working with AI (Oakly et al., 2025), avoiding what is called cognitive offloading;

- as we delegate many technical tasks to AI, we need different skills to do the remaining tasks; there will be more emphasis on social skills, creativity and agility, critical thinking and self-regulated learning

- we also need different skills to be able to oversee a team of AI agents working for us; instead of T-shaped professionals, being specialist in one area, we should become more M-shaped or X-shaped professionals: interdisciplinary integrators. These integrators are technically literate, human-centred and strategically aware.

Ebert et al. (2025b) have conducted a virtual roundtable with six renowned experts from different backgrounds and regions discuss their insights and outlooks on future learning and relevant competencies for computing. They come to similar conclusions as pointed out above. Two of their statements that summarize this are: “success will emerge when individuals move from passive learners to active creators” and “engineers will need to emerge as context-aware cocreators”.

One last point to mention is that the advent of LLMs also made it very accessible to all kinds of non-technical job roles to generate code or even complete applications. Abrahão et al. (2025) call them “citizen software engineers”. These citizen software engineers might do some of the work themselves, that they used to outsource to software engineers. Thus, it means software engineers need to be more clear on their added value, and be able to promote themselves better. In any case, I believe software engineers should play an important role in educating their non-technical colleagues how to use GenAI-tools responsibly. Software engineers can also help in setting up the technical guardrails enforcing this. The New York Times also published an article pointing out that the AI we have today requires many new technical oriented job roles to implement it safely: AI integrators, AI plumbers, AI assessors, AI personality directors, AI evaluation specialist, AI trainer, etc. This is also an opportunity for software engineers who would like to switch job roles.

LLM Landscape

Christopher Robert present a visual framework for text-based GenAI (LLMs). He divides LLM-applications in three types:

- interactive, e.g., chatbots

- autonomous, e.g. agents

- embedded (LLM behind the scenes), e.g. meeting summaries in Teams

Richard Shan (2025) sees GenAI evolving from interactive to autonomous. He summarizes this development with three key advances in GenAI:

- Self-improving RAG

- GenAI-native agents

- LAMs

RAG stands for Retrieval Augmented Generation. It is a technique that enables LLMs to retrieve and incorporate new information from external data sources, see also my previous post on LLM Engineering.

GenAI-native agents use LRMs: Large Reasoning Models or reasoning LLMs. These LRMs break down a question into smaller steps to come to a better answer (chain-of-thought [CoT] or reasoning process). Sypherd and Belle (2024) define the four components of an LLM agent: 1) a central reasoning engine, 2) planning, 3) memory, 4) tools.

LAM stands for Large Action Model. A Large Action Model is an AI system trained not just to understand language, but to take real-world actions. LLM or LRM answer questions, LAMs carry out tasks. According to ActionModel, LAMs are “the engines that can make agentic AI possible. LAMs are models trained to control computers like humans – clicking, typing, scrolling, and navigating software interfaces.”

In terms of tools the GenAI market is growing rapidly in all three major segments: hardware, foundation models and development platforms. If we zoom in on the GenAI tech stack from a SE perspective, we see several categories of tools emerging. Frameworks like LangChain and Hugging Face, vector and graph databases, orchestration tools, fine-tuning tools, embedding tools, etc. And this landscape is continuously being extended, especially with tools for building multi-agent systems. In the next section I will discuss how to put all of these tools to work.

SE4LLM: How to Build Production-Ready LLM Systems?

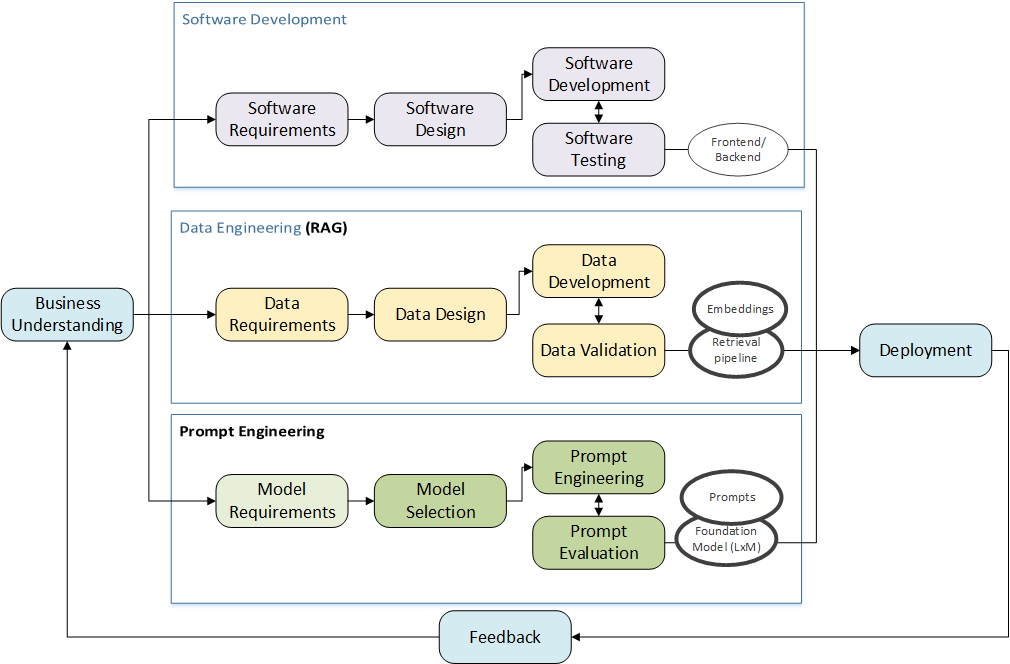

In our paper on MLOps architectures (Heck et al., 2025), we present AI engineering as a parallel process, synchronizing software, data and model engineering. This is similar for LLM engineering, although model engineering is better replaced with prompt engineering, see Figure 1.

Figure 1: LLM Engineering (RAG systems), updated from Heck et al. (2025)

In his LinkedIn post, Odax (2024) describes the hidden technical debt in GenAI systems. The foundation model (LLM in our case) is just a small part of the entire LLM system, and you need many other software components to run (and maintain!) such a system in a production-environment. This notion has introduced the new term LLMOps (as an evolution of MLOps). LLMops adapts the MLOps tech stack for GenAI use cases. Compared to MLOps, LLMOps is less focused on training models and more on optimization of computational resources for inference. A big challenge in LLMOps is that the output of LLMs is qualitative (i.e., text) and that it is just much harder to evaluate and monitor. We are starting a bigger practice-oriented research project on how to test LLM applications to build a framework with tooling to help practitioners in evaluating and monitoring their LLM-based systems.

As I pointed out in the previous section, AI agents are the next step in LLM systems. Serban (2025) analyses engineering LLM-based agentic systems, summarizing terminology, existing literature and open questions. As said, many new tools arise to support building AI agents. We now see many standardization efforts, e.g. on the protocols agents use to call tools (MCP) or to do payments (AP2). At the same time, tech companies try to build complete agent SDKs like AgentKit from OpenAI. It is too early to determine one industry standard. However it is clear that for agentic systems, LLMOps needs to evolve to AgentOps. Xia et al. (2025) presents the AgentOps Pattern Catalogue, a collection of reusable architectural solutions tailored to operational challenges of AI agents. Their catalogue is organised into seven categories: Artefact Management, Execution, Safety & Enforcement, Monitoring & Observability, Evaluation-Driven Learning, Interaction, and Assurance & Compliance. Each category addresses a specific class of operational concerns that emerge once AI agents transition into production environments.

A last consideration I would like to point to is how to arrange access to LLMs in your applications. Most of the time you would want to use an existing LLM, either open source or closed source. Hosting your own LLM is costly in terms of compute resources and not always possible. Using a commercial LLM can also be costly (pay per API call or token sent) and unwanted in terms of data protection. At Fontys ICT, we set up our own AI platform, through which we can govern the LLMs that are being used. This proprietary LLM gateway allows us to enforce policies, control access and budgets, and inform users in a unified way about the risks and limitations of the models they are using.

LLM4SE: How to Use LLM Tools for SE?

Soon after the advent of ChatGPT we saw that these LLM-based chatbots are quite good in generating code, and the advancements in that direction went really fast. Today, we have tools like Lovable and Bolt with which “citizen developers” (Abrahão et al., 2025) can generate complete applications by specifying them in natural language. This is called vibe coding, a term coined by Andrej Karpathy in 2025: “It’s not really coding – I just see things, say things, run things, and copy-paste things, and it mostly works”. Vibe coding is good way to quickly prototype ideas or build small personal projects. However, it is not very usable for building production-ready software systems. For that, you would need an extension of vibe coding to what is called vibe engineering. Vibe engineering uses developer-oriented AI-tools like Cursor, Github Copilot, Windsurf to enhance the software development life cycle while maintaining full control over code quality, architecture, and scalability. The use of such tooling shifts the software engineering process from code-centric to intent-centric. This means the software engineer spends much more time on the requirements engineering phase of the project: what do the end users want and how to specify this to the AI? For bigger projects, the software engineer will need to break down the system into smaller components (i.e., software design) that can be generated and tested independently. This decomposition task is not new in software engineering, but is crucial to stay in control of the system being generated. Finally, there is a big role for end user testing in this scenario, as the end users are the only ones who can evaluate the quality of the entire system.

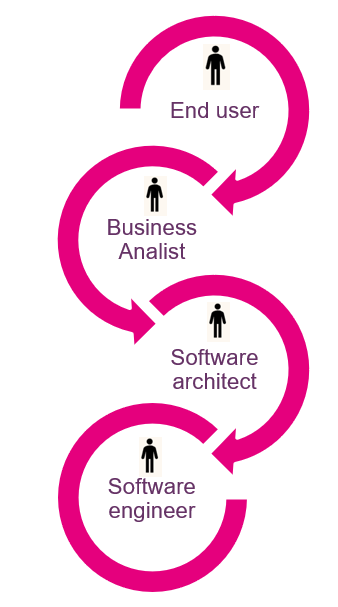

Thus, with a vibe engineering approach, the software engineer will spend less time on writing code and more time on interacting with end users and the AI in natural language. I have coined this “Human-In-The-Spiral” (see Figure 2), as opposed to Human-In-The-Loop where the end user is only considered to be interacting with the final system. Gartner sees a similar shift and have coined this User-In-The-Loop (UITL): a development workflow that requires users to be looped into any stage of the (AI) system development pipeline. This is a big shift in the role of software engineers, translating end user requirements to AI instructions, instead of code. Unfortunately, it is not really clear yet how this interaction with AI tools is done in the best way. The software engineering community is learning this by experimenting, but at the same time the tools keep changing almost weekly. As was already mentioned before, this makes it crucial for software engineers to be curious, agile and open for life-long learning.

Figure 2: From Human In The Loop (HITL) to Human In The Spiral (HITS)

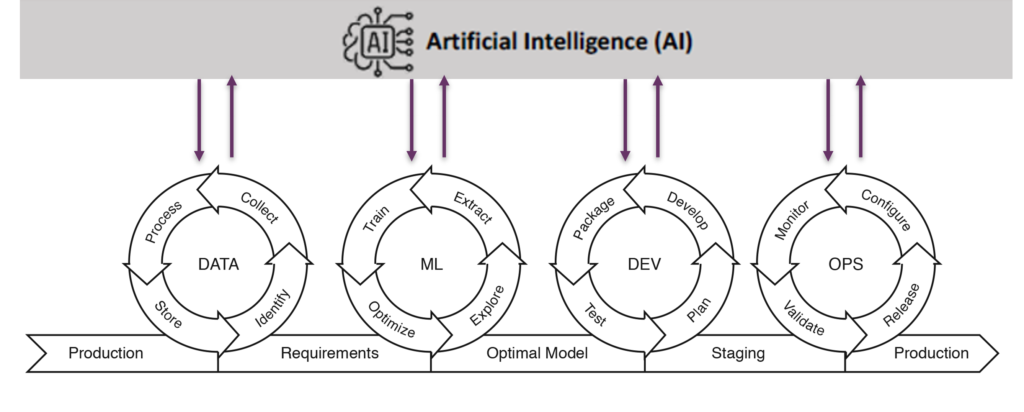

Where vibe engineering is a new paradigm with completely new tools, I also see that the traditional software developments lifecycle (SLDC) or DevOps processes are enhanced with AI-support. Ebert et al. (2025) call this DevOps 2.0: “integrating the agent-driven AI paradigm into DevOps so that AI systems can perform tasks, make decisions, and take actions throughout the software development lifecycle without continuous human intervention, making the process more efficient, scalable, adaptive, and quality assured”. For this, existing tools are being extended with genAI capabilities, like Sonar AI solutions and Visual Studio Code. As is depicted in Figure 3, this is not just for generating code, but also for other activities in the DevOps or AI Engineering (MLOps) process.

Several authors (Terragni et al., 2025; Shafiq et al., 2012; Durrani et al., 2024; Jin et al., 2024) have given an overview of use of AI, ML and LLMs for software engineering activities. Although most of the solutions they describe are still at a low Technology Readiness Level (TRL), it does give an impression of the many different activities that are being researched for enhancement with AI-support. From requirement generation, to code review, to test case generation to program repair, and many more. As said more and more solutions do reach the higher TRLs, and can be used by software engineers to build production-ready software.

Also frameworks and standards are being updated, such as the Certified Tester certification by ISTQB, which now has a certification for Certified Tester Testing with Generative AI. That indicates that GenAI, LLMs are here to stay and impact the entire SE lifecycle. How the tools are to be used effectively and on large scale is not clear yet, but it is clear that software engineers should start experimenting now, preferably in an organized way within their own organization. You can only incorporate the newest AI-tools effectively if you are in control of your software engineering processes.

Figure 3: AI4AI – AI (LLMs) can play a role in each step of the AI engineering or DevOps process

Conclusion

This blogpost gives my software engineering perspective on what is going on with recent AI developments. It is essentially an organized overview of related work on SE4LLM and LLM4SE, as LLMs are the most fundamental AI-development from an SE perspective. If you are more interested in a visual overview, contact me. Then I can send you my slide deck of collected pictures from all of the above publications. My slide deck is being continuously updated, and this post might lag behind a bit. If you miss important links in my analysis, please also let me know. Together we can explore the future of software engineering.

References

Silvia Abrahão, John Grundy, Mauro Pezzè, Margaret-Anne Storey, and Damian A. Tamburri (2025) Software Engineering by and for Humans in an AI Era. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 34, 5, Article 129, 46 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3715111

K. Durrani, M. Akpinar, M. Fatih Adak, A. Talha Kabakus, M. Maruf Öztürk and M. Saleh (2024) A Decade of Progress: A Systematic Literature Review on the Integration of AI in Software Engineering Phases and Activities (2013-2023), in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 171185-171204 https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3488904

Dellermann, P. Ebel, M. Söllner, et al. (2019) Hybrid Intelligence.Bus Inf Syst Eng 61, 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-019-00595-2

Ebert, G. Gallardo, J. Hernantes and N. Serrano (2025a) DevOps 2.0 in IEEE Software, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 24-32, https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2025.3525768

Ebert et al. (2025b) Beyond Code: Competences for the Future of Computing. Computer, vol. 58, no. 11, pp. 18-27. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2025.3600944

Heck, J. Snoeren, M. Veracx, and M. Peeters (2025) An Approach for Integrated Development of an MLOps Architecture. In: Andrikopoulos, V., Pautasso, C., Ali, N., Soldani, J., Xu, X. (eds) Software Architecture. ECSA 2025. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 15929. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-032-02138-0_1

Jin, L. Huang, H. Cai, J. Yan, B. Li, and H. Chen (2024) From llms to llm-based agents for software engineering: A survey of current, challenges and future. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.02479.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2025) Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

Shafiq, A. Mashkoor, C. Mayr-Dorn and A. Egyed (2021) A Literature Review of Using Machine Learning in Software Development Life Cycle Stages, in IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 140896-140920 https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3119746

Shan (2025) AI That Learns, Thinks, and Acts: The Next Frontier of Generative AI, in Computer, vol. 58, no. 10, pp. 28-39. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2025.3582568

Sypherd, & V. Belle (2024) Practical considerations for agentic LLM systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.04093.

Valerio Terragni, Annie Vella, Partha Roop, and Kelly Blincoe (2025) The Future of AI-Driven Software Engineering. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. https://doi.org/10.1145/3715003

Boming Xia, Yue Liu, Qinghua Lu, Liming Zhu, and Dino Sejdinovic (2025) AgentOps Pattern Catalogue: Architectural Patterns for Safe and Observable Operations of Foundation Model-Based Agents https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5534588

Vind ik leuk

Vind ik leuk

Over Petra Heck

Petra werkt sinds 2002 in de ICT, begonnen als software engineer, daarna kwaliteitsconsultant en nu docent Software Engineering. Petra is gepromoveerd (kwaliteit van agile requirements) en doet sinds februari 2019 onderzoek naar Applied Data Science en Software Engineering. Petra geeft regelmatig lezingen en is auteur van diverse publicaties waaronder het boek "Succes met de requirements".